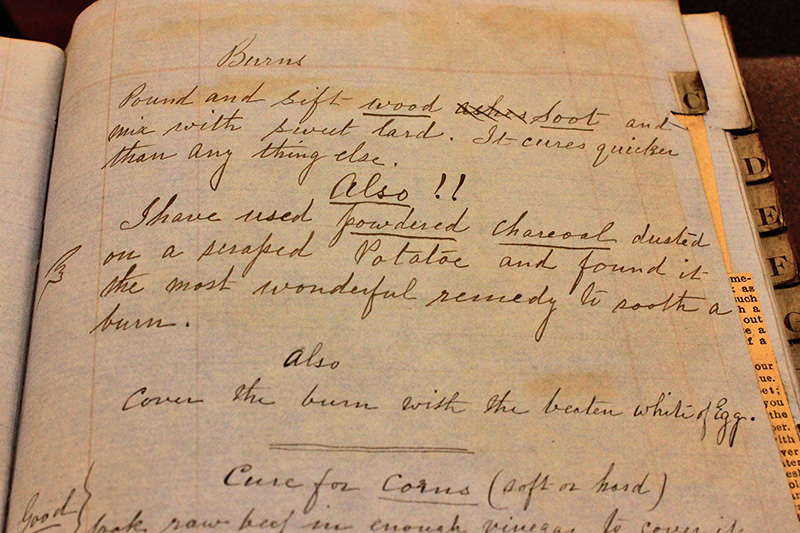

Wood soot and egg whites: Emma Burke Gilson’s recommended remedies for burnscourtesy california historical society

Wood soot and egg whites: Emma Burke Gilson’s recommended remedies for burnscourtesy california historical societyFirst published in April 2020. A few years ago, I discovered my great-great-grandmother’s home remedy book. In the mid-1860s, she had started filling a ledger with handwritten notes and newspaper clippings about fixes for household problems and treatments for a wide range of ailments.

The entries, tabbed alphabetically, covered everything from ants to warts. Most of the maladies listed were common bothers—back pain, chapped lips, chest colds, chilblains, dyspepsia, earaches, flatulence, freckles, mosquito bites, nose bleeds, poison oak, toothaches, sleeplessness. The remedies, wacky and unscientific, were variously described as “perfect,” “sure,” and “excellent.”

To relieve a sore throat, the book recommends “salt pork or fat bacon sliced &To relieve a sore throat: “salt pork or fat bacon sliced & simmered in hot vinegar, applied to the throat as hot as possible.” simmered in hot vinegar, applied to the throat as hot as possible.” One all-purpose formula promises “to remove Grease spots from any thing & to kill Bed bugs.” A doodle of a hand points to this emphatic entry: “Also!! I have used powdered charcoal dusted on a scraped Potatoe [sic] and found it the most wonderful remedy to sooth a burn.”

While herbal ingredients abound, the recipes routinely call for less wholesome substances like borax, saltpeter, paregoric, and caustic potash. Black teeth? Brush them with honey and muriatic acid. Poor appetite? Try quinine mixed with strychnine. A sure remedy for “low spirits”: Lavender water and hartshorn, an aqueous solution of ammonia.

The other day, I looked at the book again, and a few entries I’d previously overlooked popped out. Alongside the everyday nostrums are treatments for potentially deadly conditions like whooping cough and scarlet fever. There’s “a sure cure for diphtheria” and clippings suggesting ways to alleviate smallpox. An intricate “East India cure for cholera” is written out by hand, a dried leaf still pressed against its margin.

I do not know if my great-great-grandmother had occasion to try any of these, but she had good reason to keep them at hand. When she was nine, her family had sailed from Tasmania to San Francisco, only to have their prospects dashed when her father died from dysentery. (The drinking water in Gold Rush-era San Franciscowas a bitch.) Throughout the late 19th century the city experienced bouts of cholera, smallpox, and bubonic plague.

Keeping a remedy book was an act of self-defense, a bulwark against the terrors of a world without germ theory or antibiotics or childhood vaccines. The earliest entries in my great-great-grandmother’s remedy book coincide with the 18-month period in which her first two children died in infancy.

Life was uncertain, death was arbitrary. That feeling of vulnerability does not seem so alien at this moment.

A remedy book was a bulwark against the terrors of a world without germ theory or antibiotics or childhood vaccines.The impulse to shore up our psychological defenses against the unknown is particularly acute right now. Our tabs, feeds, chats, and inboxes have become digital remedy books where we collect and exchange the latest tidbits of information that might shield us and our families from infection. Should we stand 6 feet apart—or 9… or 20? What kind of mask should I wear? Should I quarantine the groceries? Disinfect the mail? Prophylactically nuke the takeout pad thai? Maybe a little gargling, zinc, elderberry, or CBD wouldn’t hurt…

You can see how an ounce of prevention can snowball into an avalanche of hooey. Some of the bogus notions currently out there—like bathing in Clorox to kill the virus—sound as if they came straight out of the Victorian era. (The remedy book recommends sponge baths of carbolic acid to cure smallpox and scarlet fever.) No one embodies the desperation for a miracle COVID-19 cure more than the president. Hydroxychloroquine! Injecting disinfectant! Damn the double-blind testing and unfortunate side effects, what have you got to lose?

Trump’s magical thinking has made him a laughingstock. The cluelessness that suffuses my great-great grandmother’s remedies is of a different, forgivable kind. While her generation had abandoned the heroic medicine of the recent past, with its purges and bloodletting, it was still grasping at a scientific understanding of health. She was living on the cusp of an era of discovery; she just didn’t know it. While her remedy book’s unintentional goofiness still entertains me, I find its sense of resolve reassuring. We don’t really know what the hell is going on, but we’ll do our best to maintain a sense of control until we get there.

My great-great-grandmother, Emma Burke Gilson, beat the odds. She died when she was 80, having outlived eight of her nine siblings and surviving the 1918 flu pandemic. I wonder if she attributed her longevity to an occasional dose of honey and ginger mixed with freshly shaved iron filings—“An excellent Tonic for the Blood.”