In early 1918, a Russian émigré calling himself Maurice Fruit enrolled as a freshman at the University of CaliforniaFirst published by California magazine. , Berkeley. The 26-year-old threw himself into campus politics, helping organize a socialist club and announcing to a dean that he was “thoroughly in sympathy” with the Bolsheviks who had just seized power in Russia. He claimed to have been friends with Leon Trotsky before coming to the United States.

It was a risky time to be an outspoken radical: The country was sending off young men to fight in Europe, and Berkeley was the center of a clash between pro-war patriots and antiwar leftists. It was even riskier for a wanted man.

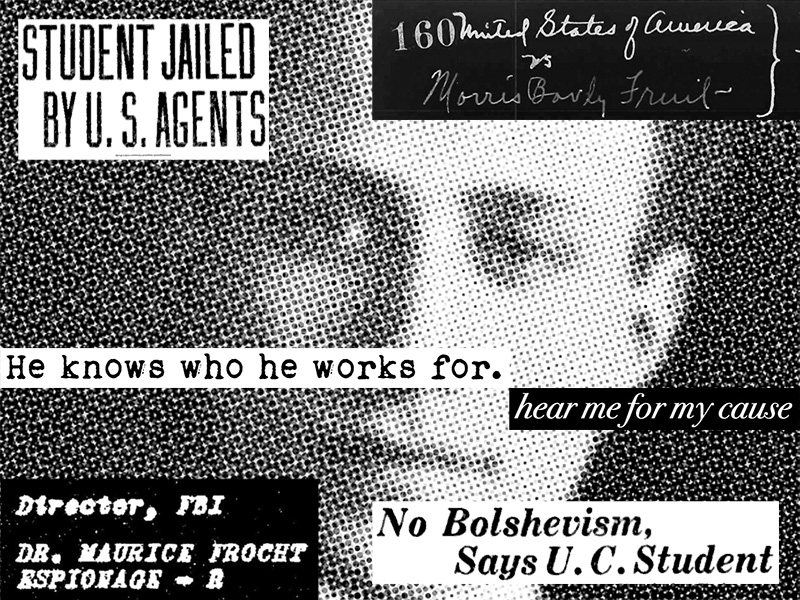

Fruit was on the run, having neglected to register with his local draft board back in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The Bureau of Investigation, the FBI’s predecessor, which had been aggressively tracking suspected subversives, was looking for him. On February 27, 1918, the Berkeley police arrested Fruit and handed him over to the U.S. Marshal. He was then taken to San Francisco and charged with draft evasion.

The local newspapers went wild. A front-page article in the San Francisco Chronicle described him as a “Russian radical” and “anarchist propagandist.” The police reportedly found links to draft resisters and pacifists in his room on Atherton St., as well as clippings about Emma Goldman’s recent trial for obstructing the draft. So much evidence was supposedly seized, that the arrest of 42 more agitators was said to be imminent.

The papers also suggested that Fruit was up to something more sinister. Why else would he own a red flag, ammunition, and an 1865 newspaper with a “detailed account” of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln? He allegedly had been taking notes on factories and “war work plants.” He didn’t like his landlady bringing laundry into his bedroom, yet “he had many callers, among them a woman.”

And he had gone by several names, including Morris Fruit, Maurice Frocht, Morris Baveley, Maurice Bavly, and Fred Maurice.

Berkeley police chief August Vollmer tried to tamp down some of the wilder rumors about Fruit. “There is nothing in his papers that would incriminate him in a plot against the United States government,” Vollmer told The Daily Californian. “Reports of his anarchism are apparently erroneous.”

• • •While Fruit may not have been a fanatic, he seems to have anticipated the day when he’d have to prove his commitment to his beliefs—and test his loyalties. Tellingly, his 1917 high school yearbook page had quoted the opening of Brutus’s speech in William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar: “Romans, countrymen, and lovers! Hear me for my cause, and be silent, that you may hear.” In it, Brutus justifies his decision to plot to kill the dictator, casting the betrayal of his friend as an act of patriotism: “Not that I loved Caesar less, but that I loved Rome more.”

Though he had initially claimed to be 32 and beyond conscription age, Fruit’s resistance melted once he was brought before a federal commissioner. He waived his right to an attorney and stated that he “had now changed his mind sufficiently to be ready to serve the United States if called.” On March 5, Fruit paid $500 bail and was released. A few days later, the charges against him were dropped.

The Daily Cal interviewed Fruit after he returned to campus. Fruit didn’t let on that he’d apparently made a deal to avoid prison time. “There is no disgrace in being a political offender,” Fruit stated. “The greatest men of history were for some reason or other political offenders.”“There is no disgrace in being a political offender,” he stated. “The greatest men of history were for some reason or other political offenders.” He sounded energized by his brush with the law. His treatment behind bars had been “very good indeed” and he had “learned more about crime as a social problem than [one] can learn in one semester in college.”

Fruit claimed that he had long been a radical. “[E]ver since I was nine years old when I was forced to eat a piece of pork as punishment for being a Jew,” he said. After being compelled to leave Russia and Germany due to his socialist politics, Fruit turned to America, which he pictured as “the embodiment and symbol of justice and equality.”

After completing a semester at Cal, Fruit joined the Army. On October 14, 1918, Fruit, now attached to a medical unit, became a naturalized citizen under the name he’d use for the rest of his life, Maurice Frocht. (He had immigrated in 1911 under the name Moses Frocht.)

He swore loyalty to the United States and formally renounced his “allegiance and fidelity” to “the present government… of Russia.” He attested that he was not a member of any group that opposed “organized government.”

Fruit would no longer make headlines, but his flash of notoriety in Berkeley was not the last time he’d have to choose between his principles and self-preservation.

• • •After the war ended, Fruit returned to Michigan, got married, and earned a medical degree. He then moved to New York City, setting up practice as a neuropsychiatrist. In 1930, while visiting family in Europe, he decided to visit the Soviet Union, which, he later said, he believed “was building a new and better country and a better world.” In Moscow, he met up with Cyril Lambkin, a fellow émigré whom he’d known in Michigan. Lambkin, a member of the Communist Party, was a manager for Amtorg, the Soviet Union’s official trading company in the United States. Lambkin used his connections to show Fruit around, taking him to visit hospitals, factories, and Lenin’s tomb. After they returned to the States, Lambkin recruited Fruit to set up a medical office for Amtorg’s employees in New York.

Much of the part-time work Fruit did for Amtorg was routine, treating staff and hobnobbing with visiting dignitaries. Yet even as Amtorg operated Fruit’s codename was “Doctor.”

His Soviet intelligence file stated,

“He knows who he works for.”as a legitimate business, it was also a cover for espionage. Was Fruit a spy? The Russian agents he worked alongside clearly saw him as an asset: According to Soviet intelligence files that were made public after the end of the Cold War, Fruit “[p]rovided us with passports,” an apparent reference to Soviet efforts to procure and forge American passports. His codename was “Doctor.”

Fruit also “conducted a number of operations” that were not detailed in his Soviet file. An episode he later recounted shows how the line between his official duties and clandestine work might have blurred. In 1933, the head of Amtorg asked Fruit to administer an injection to an employee who had gone “berserk” so that he might be “shipped on a Russian boat back to Russia.” The man may have been mentally ill, though it’s possible that he had been recalled to the Soviet Union to be imprisoned or executed. Frocht claimed that he had refused to tranquilize the man, though he did agree to accompany him back to Moscow.

In 1935, Fruit sued Amtorg for unpaid wages and cut his ties with the organization. His Soviet intelligence file notes that he was “canned” due to a “bad relationship” with a higher-up. Yet whoever wrote his entry didn’t question his obedience. “He knows who he works for,” they concluded.

For the next two decades, Fruit lived a respectable life, teaching at Columbia University and practicing from his apartment on the Upper West Side. In 1942, he registered for the draft without protest.

Then, in May 1951, two months after Ethel and Julius Rosenberg were convicted of being Soviet spies, the FBI’s New York office opened a file on Fruit, tagged “Espionage-R.”

• • •An informant had mentioned Fruit’s involvement with Amtorg and claimed that he’d had “important underground connections.” The agency put together a dossier, compiling information on everything from the car Fruit drove (a black 1947 Chevrolet) to his “peculiarities” (he’d lost vision in one eye in an auto accident). Agents logged his mail and phone calls and watched his apartment. They asked their sources—including Whittaker Chambers, the former communist who had testified against alleged Soviet agent Alger Hiss—if they’d known Fruit. Most did not, and none could identify him as a Communist Party member or sympathizer.

In late 1952, FBI agents interviewed Fruit, and found the short, balding doctor, now 61, “sincere in his offer to cooperate.” He volunteered detailed information about his time with Amtorg, including details about his bosses and colleagues. (He reported that the Amtorg official with whom he’d argued over the “berserk” man had gone back to Russia and was “liquidated.”) Fruit even handed over photos and films he’d held onto since the 1930s—perhaps as leverage to use at a moment like this.

Confronted with his past, Fruit took a similar approach to the one that had gotten him off the hook in 1918: He acquiesced to the authorities without fully disavowing his beliefs. Fruit assured the FBI that his youthful politics Two months after the Rosenbergs

were convicted of being Soviet spies, the FBI opened a file on Fruit, tagged “Espionage-R.”were “purely socialistic, not communistic.” He admitted that he’d been sympathetic to the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s, “but became disillusioned after working with the Russians.” (The informant who originally named Fruit reported that he’d once said “it would be necessary ‘to have another Russian Revolution to clean up the mess of the first revolution.’”)

Fruit was open about having been a fellow traveler, but he did not want to be seen as a mindless follower: He wasn’t like his erstwhile friend Lambkin, who “had blind faith in the party and was capable of performing any task assigned to him regardless of whether he agreed with the order or not.” Fruit told the FBI that he was now “strongly anti-Russian” and hoped “President-elect Eisenhower will stop these Russians as well as Russian agencies in the U.S.”

Even as Fruit spilled the beans, he didn’t confess everything. He was silent about passport fraud and other illegal “operations.” When asked if he knew anything about Trotsky’s assassination, he did not mention that he’d once known—or claimed to have known—the exiled revolutionary. And he never revealed that he’d once been known as Maurice Fruit. As a result, the FBI did not find out about his time in Berkeley, his draft evasion case, or the Bureau of Investigation’s file on him. Even as he demonstrated his loyalty to his country, Fruit proved his allegiance to himself.

Unlike Brutus, Fruit would not have to fall on his sword. Assisting the feds ensured that he would live without the fear of scrutiny or prosecution. But it did not buy him much time. The FBI closed Maurice Fruit’s file in December 1956. He died six months later.