Stark Alley, the dead-end street where Doughnut Sal lived and died.dave gilson

Stark Alley, the dead-end street where Doughnut Sal lived and died.dave gilson

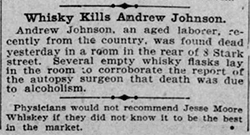

In December 1902, the San Francisco Chronicle ran a light-hearted article about the city jail’s “regulars.” This was a crew of habitual misdemeanants with nicknames like Happy Hooligan, Dago Mary, and Weary Willie, who were purported to “have spent all but a few weeks of their time for the last ten to twenty-five years in jail.”

“The mystery of ‘the regulars’ is represented by an old person called ‘Doughnut Sal’ who makes the jail her home,” continued correspondent Jeanne E. Francoeur. Sal’s moniker came from “her abnormal love of doughnuts and her desire to show everyone how to make them. It is the only subject on which she will talk.”

An artist’s rendering of “Doughnut Sally” showed a weathered woman with a hawkish nose and a glare to match. “All that is known of her is that she has a bank account, a high-sounding name, a good deal of property, and a horror of spending a cent except for cheap whisky,” Francoeur wrote, adding uncharitably, “she also has the palsy and a complexion like Parma violets after they have been relegated to the trash barrel.”

“An old person called ‘Doughnut Sal,’” one of the county jail’s “regular boarders”san francisco chronicle

While Francoeur suggested that Sal epitomized an inexplicable “class of people who wish to go to jail,” the reality was that Sal, like her fellow jailbirds, was an alcoholic whose main offense was violating the city’s preposterously broad anti-vagrancy law.

And Doughnut Sal was an even more intriguing figure than Francoeur might have imagined. By the early 1900s, she had made a name up and down Northern California. Unrelated, but too good not to share: This ad posted in 1916 by Francoeur shows that freelancers have been paid in publicity for at least a century. She’d amassed and lost a small fortune, may have faked her own death, and likely had the distinction of being the first woman to run afoul of California’s inaugural anti-prostitution law.

She’d amassed and lost a small fortune, may have faked her own death, and likely had the distinction of being the first woman to run afoul of California’s inaugural anti-prostitution law.

Now as then, it’s tempting to see Sal as a character, an old-timer with a funny nickname and a gritty biography. We should resist that urge, if only because there’s not much record of her personality—whether she was sassy, salty, or sour. And from what hints do remain of Sal’s life, especially her final years in San Francisco, it doesn’t sound like it was a fun one. Desperation and squalor shouldn’t be confused with eccentricity or color.

Still, the tale of Doughnut Sal is a fascinating dose of anti-nostalgia, a reminder that being down and out San Francisco has always sucked. So grab a vegan organic doughnut and a single-origin pour-over and let’s get started.

“A woman of bad repute”

Before she was Doughnut Sal, she was Sarah J. Folsom. She was born in 1833 into an old New Hampshire family that could trace its roots to “an ancient one in England.” In 1853, she emigrated from New Hampshire to Northern California. Her younger brother, George Washington Folsom, arrived the same year. According to family lore, he made it only after surviving a shipwreck and hiking across the Isthmus of Panama. There’s no word on whether Sal accompanied him on this trek. Her father and older sister also relocated to California, but she became estranged from her family, for reasons that will be obvious. One of her great-grandnieces told me that she only learned of Sal’s existence last year; she was never acknowledged or discussed by the family.

What may be the first mention of Sal in Northern California newspapers was in June 1855, when the Sacramento police, in the words of the Daily Union, “made a descent on the houses of ill-fame throughout the city.” A woman identified as Sarah Jane Folsom was arrested along with dozens of other suspected prostitutes, including “forty-eight China women.”

Folsom earned the distinction of being the first woman charged under California’s new anti-brothel law. She was fined $127.She was quickly found guilty of violating the state’s recently enacted anti-brothel law and fined $127. Though it went unremarked at the time, this earned Folsom the distinction of being the first woman charged under the new law. Not long afterwards, she was fined $37 for “interchanging vuglar and obscene language within hearing of ears polite.”

By the late-1850s, Folsom had acquired the deep-fried, caffeinated nickname attributed to “the fact that she lives as a rule on doughnuts and coffee.” The earliest reference to “Doughnut Sal,” in a 1858 item from California’s Gold Country, reports that she “caused a water jug to come down on the head of Wilson which caused him to bleed like a stuck pig.”

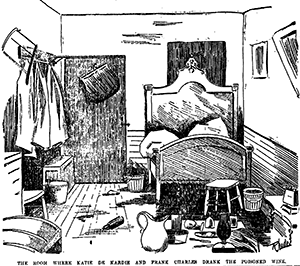

A room on Stark Street, the alley where Doughnut Sal lived her final years.san francisco chronicle

A room on Stark Street, the alley where Doughnut Sal lived her final years.san francisco chronicle

For the next few decades, Folsom lived a somewhat peripatetic existence. The 1860 Census found her in the gold town of Marysville, living with a 36-year-old male cook. She reported owning $3,000 worth of real estate and $200 of personal property. Trouble contuinued to find her. In 1866, she was cited for unpaid taxes. Two years later, she was arrested again in Sacramento, this time for “enticing people into a house of ill-fame.” She failed to appear in court and forfeited her $10 bail.

Sal moved to the Salinas Valley, where a weird and unsettling episode occurred. As an item in the San Francisco Call in January 1871 described it:

Murder in Monterey County.— Sarah Folsom, sometimes called “Doughnut Sal,” a woman of bad repute, who lived near Natividad, Monterey county, is missing and it is supposed she has been murdered. A horse tied near her house was found starved to death and a dress belonging to her was found in her house stained with blood with holes that appeared to have been made with a knife.

A longer story on the “dreadful mystery” from the Salinas Standard reported that Sal had “been in the habit of visiting from time to time the neighboring towns for the purpose of prostitution.” A man who had accompanied her on these trips was also missing. The authorities appealed to the public for clues.

The return of Doughnut Sal

Less than a month later, she turned up in Marysville again, apparently unharmed:

NOT DEAD YET. — Sarah Folsom, alias “Dough-nut Sal,” so mysteriously murdered, a few weeks ago, by the Salinas Standard, near Natividad, has come to life again, and at present is in this city.

She was not eager to explain the troubling scene she’d left behind. Had she been attacked—or had she attacked someone? Had she tried to stage her own death? She would only state that “[o]f the bloody evidence of murder found in the house she knows nothing.”

In August 1874, the San Francisco Bulletin singled her out, a bit mockingly, as the most memorable guest at “the grand summer fandango of the Piutes [sic]” in central Nevada:

Doughnut Sallie was the belle of the occasion. Her dress was of striped calico, which was imported expressly for her by Koenigshofer at a cost of a bit a yard, with rabbit-skin flounces and overskirt of bedticking. Her feet were encased in army brogans, gracefully adorned with bows of red flannel. Hair, au naturel. [...] Her shoulders were covered by a magnificent opera-cloak, made of red blanket and trimmed with a fringe of caterpillars.

Adorned in this patchwork couture, Sal was “the admired of all admirers.” A few years later, she was still in Nevada’s silver country, described as one of a trio of local “celebrities” that included Carroty Jane and Toe Jam Annie.

By the mid-1880s, Sal had returned to Sacramento, getting charged with “enticing” and “exhibiting.” (The word “prostitution” is never seen in these old accounts.) In March 1894, she was found guilty of vagrancy, even though she proved to the court that she had $900 in a San Francisco bank. She was let go only after she agreed to leave town.

Not long afterwards, the former “soiled dove” was reported to be back in Marysville, looking like “a miserable wreck” and unnerving children and young men alike:

An old woman whose face was painted an ashy white and whose shaky frame denoted that whisky had the best of her, attracted considerable attention on the streets yesterday. It was not the shawl she wore or her unsteady gait that attracted attention at first, but it was an awful painted face so seldom seen except on a clown at a circus.

One old-timer identified the “ghostlike” figure for the curious: “the old girl’s name is ‘Doughnut Sal.’”

Later that year, she resurfaced in San Francisco, where she would spend the last years of her life. A wagon driver was reported to be “the most successful of Doughnut Sal was “so penurious that she haunted the saloons on the Barbary Coast and begged money” despite being worth a rumored $30,000.‘Doughnut Sal’s wooers”—a jokey reference to her reputed profession, alleged wealth, or both. The Call reported that “she was so penurious that she haunted the saloons on the Barbary Coast and begged money from the frequenters” despite being worth a rumored $30,000. (That would be more than $800,000 today.) When she was arrested for vagrancy in October 1899, she managed to sneak $20 into the city jail.

The original source of Sal’s wealth is not clear, but she clearly had significant means at one time. In a 1876 suit filed in San Francisco, she alleged that she’d lost $4,000 when she made a deposit in the Adams Bank in three days before it failed in 1855. She belatedly sued the bank’s directors for fraudulently taking her money. According to one article, she recovered $12,000; another says a jury found in favor of the bank.

Despite her apparent stash of assets, Sal was repeatedly charged as a vagrant. In January 1900, Acting Police Chief W. J. Biggy ordered his officers to “make a daily note of all known or suspected vagrants,” paying “particular attention to all known or suspected frequenters of houses of ill-fame and hangers-on about saloons of questionable character.” Under the city’s catch-all anti-vagrancy code, charges could be brought not just against the homeless, but the unemployed, beggars, loiterers, midnight wanderers, and “every common prostitute and common drunkard.” The maximum punishment was six months in jail. The law was applied broadly and often: “Jack the Ripper,” an otherwise “inoffensive” young man prone to getting violently drunk, was reportedly sentenced 115 times in just seven years.

In her account of the jailhouse regulars, Francoeur claimed that repeat offenders like Sal were locked in a friendly rivalry with the city’s legal system. “The Police Judges become so weary of sentencing them,” she wrote, “they frequently ask the prisoners, ‘Well… “Doughnut Sal,” how long do you want now?’” Perhaps, but it seems unlikely that Sal fared so well in front of magistrates like Judge Alfred J. Fritz, who sentenced her to 10 days in 1900. Here’s the Call’s account of an exchange between Fritz and a “middle-aged and slovenly” woman brought before him on a vagrancy charge a few years later:

[Woman:] “…Now go ahead and prove me a vag.”

“What do you think you are?” inquired the court.

“Thinking ain’t no law […] Only what we know is law; and I know I’m a workin’ lady.”

“You work every one you can,” remarked his Honor, “and I’ll give you thirty days in jail to think up some more law.”

Sal’s final years

Even if she spent a good deal of time behind bars, Sal managed to keep a room on Stark Street, a dead-end alley off of Stockton Street, in northwestern Chinatown,  San Francisco’s red-light district in 1899."san francisco's zone of prostitution, 1880–1934"right inside the city’s semi-official prostitution district. (One study estimates that there were no fewer than 70 brothels within two blocks of Stark.)

San Francisco’s red-light district in 1899."san francisco's zone of prostitution, 1880–1934"right inside the city’s semi-official prostitution district. (One study estimates that there were no fewer than 70 brothels within two blocks of Stark.)

Stark Street, formerly called Polk Alley, was one of the many San Francisco side streets that only made it into the news as backdrops for drunkenness, destitution, and violence. Among the various mentions of Stark/Polk around the time that Sal lived there: A tourist “crazy drunk” from “strong potations of Barbary Coast whisky” jumped through a window and ran off “yelling like a Sioux Indian”; a young man “succumbed to the wiles of an aged and demoralized member of Circe’s wicked legions” only to be attacked by her husband; a man died after drinking sulphuric acid, purportedly “mistaking it for wine”; a police raid on the residence of two suspected burglars revealed “a quantity of plunder stolen from barber shops”; an African-American woman set fire to a room in a two-story tenement “in a spirit of drunken revenge”;Another booze-fueled tragedy on Stark Street, and evidence that keyword-based ad placement has always been terrible. an elderly alcoholic known as “Old Moses” was severely burned when he attempted to light a fire on the floor of his room; a Brazilian tamale vendor died penniless and alone; a “miser” found dead in his “wretched room” was discovered to have had $5,000 in the bank.

an elderly alcoholic known as “Old Moses” was severely burned when he attempted to light a fire on the floor of his room; a Brazilian tamale vendor died penniless and alone; a “miser” found dead in his “wretched room” was discovered to have had $5,000 in the bank.

In its coverage of a young alley resident poisoned by her lover, the Chronicle described the cul de sac as “just such a place as Victor Hugo would select for the scene of one of his mysteries.” One side was taken up by a “dilapidated” two-story building of single-room apartments that “present much the appearance of cells.” In 1902, child-welfare officials found a couple and three children living in “abject poverty” in a “room eight feet square” on the alley. The 1900 Census records for Stark Alley show that many residents were immigrants. Most of the men were laborers; many of the women were washerwomen or, like Sal, gave no occupation.

Sal would live out her last days amid this grinding poverty. When she was charged with vagrancy in 1900, the police officers who brought her in testified that her rented room was “filthy in the extreme.”

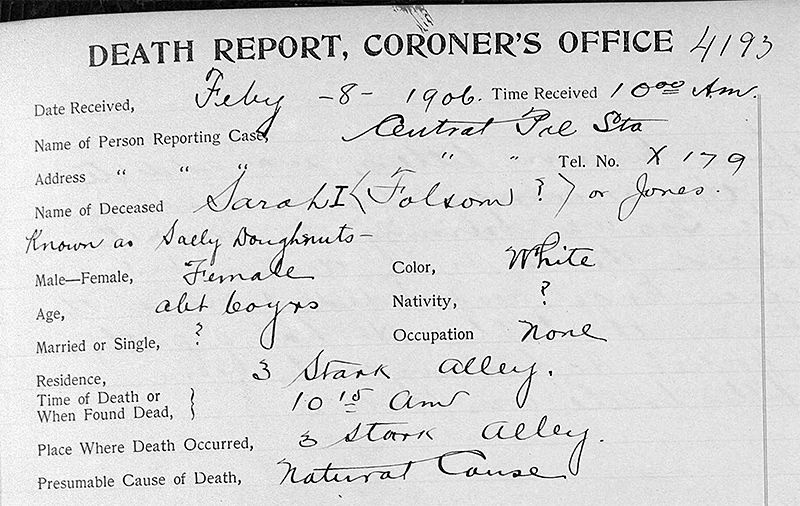

The building that now stands where Doughnut Sal used to live is currently valued at $3.7 million.Sal was found dead on February 8, 1906. According to the coroner’s report, a firefighter discovered her around 10:15 that morning. “She was lying in a filthy mess of old clothes, a broken lounge was alongside of her, from which she had evidently fallen off.” An autopsy concluded that she had died from pneumonia and chronic heart disease. The papers ran short items on her death. “In her prime she was known as one of the leading members of the half world,” the Call wrote in a short notice on the passing of “Sally Doughnuts.” “She was possessed of considerable wealth at one time.”

Two dollars were found in her clothing, along with a ring and a pair of earrings. The public administrator found a bank book in her clothes; the Chronicle reported that it recorded $200 in savings, “the remains of her one-time prosperity.” It seems to have been enough for a decent burial. The now unmarked grave of Sarah J. Folsom, AKA Doughnut Sal, is in a shady corner of Greenlawn Memorial Park in Colma. There are four doughnut shops within a five-minute drive.

The death of Sarah Folsom, “known as Sally Doughnuts”

Thanks to Marylin Cutting and Lori Scherr for their assistance.