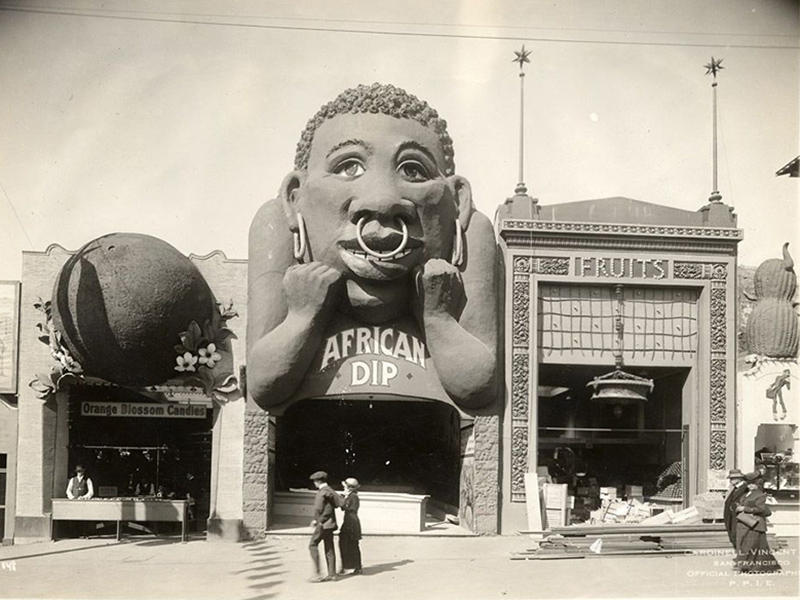

The African Dip at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Expositionsan francisco public library

The African Dip at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Expositionsan francisco public library

In 1915, tens of thousands of San Franciscans passed this enormous figure of a stereotypical savage as they strolled the Joy Zone, the amusement area at the eastern end of the city’s Panama-Pacific International Exposition. The 3,360-foot long midway** “The Zone” was located between Fillmore and Van Ness Streets. The African Dip was not far from the current intersection of Franklin and Bay Streets. (Soakum was near what’s now the Marina Branch Library.) was lined with rides, games, food stands, and diversions such as a working scale model of the Panama Canal, an ostrich farm, and baby incubators. Yet even by the sensational standards of the Zone, the African Dip’s façade was grotesque, forcing passersby to wonder what exactly was happening in the shadows beneath.

A century later, it is still impossible to not wonder what went on inside this repulsive yet intriguing building. The answer is surprising, though somewhat mysterious since little has been written about the attraction, its origins, or how people reacted to it. What can be pieced together involves racist carnival games, cameos by “the Rockefeller of vaudeville” and a creepy “monkey man,” and a glimpse into the uglier side of San Francisco’s celebrated exposition.

What was the African Dip?

Many fairgoers who saw the African Dip would have known right away  “Amusing to All but the Victim.” Popular Mechanics, 1910 google books

“Amusing to All but the Victim.” Popular Mechanics, 1910 google books Ad in The Billboard, 1911 internet archivethat it referred to a popular carnival game of the same name, a dunk tank where the contestants were white and the target was black. Sometimes the man perched over the tank would taunt the contestants into throwing more balls (and spending more money). The game was also known as Coon Dip or N****r Dip; as one slogan put it, “Hit the Trigger, Drop the N****r.” These dunking booths were just some of the many of late-19th century and early-20th century games that featured African-Americans as actual or symbolic targets, including a vicious fairground game in which contestants hurled baseballs at the heads of live targets—the African Dodger.

Ad in The Billboard, 1911 internet archivethat it referred to a popular carnival game of the same name, a dunk tank where the contestants were white and the target was black. Sometimes the man perched over the tank would taunt the contestants into throwing more balls (and spending more money). The game was also known as Coon Dip or N****r Dip; as one slogan put it, “Hit the Trigger, Drop the N****r.” These dunking booths were just some of the many of late-19th century and early-20th century games that featured African-Americans as actual or symbolic targets, including a vicious fairground game in which contestants hurled baseballs at the heads of live targets—the African Dodger.

When the African Dip game was introduced around 1910, Popular Mechanics heralded it as an improvement on the African Dodger, which had become “too old and commonplace.” Not to mention that it wasn’t always easy to find African-American men or boys for such degrading and dangerous work. The Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia has documented the injuries suffered by dodgers, including broken teeth and noses, skull fractures, and fatal internal damage. And public opinion in some places was turning against the game. A New Jersey newspaper ascribed the invention of the African Dip to the “progressive era.” New York passed a law banning race-based “ball dodger” games in 1917. (Nonetheless, Chicago’s Riverview and other amusement parks had African Dip-type games as late as the 1950s and 1960s.)

The above photo of the African Dip from the San Francisco Library’s collection has “African Dodgers” written on the back. Yet this appears to be inaccurate.* * Were there ball dodgers elsewhere at the expo? An anecdotal item in the San Francisco Chronicle in 1915 quoted a black man who said he was “th’ great African Dodger in Toyland,” a large amusement area in the Zone.In spite of their names and exteriors, the San Francisco exposition’s African Dip and its similarly-topped twin, Soakum, featured neither live targets nor racist dunk tanks.

An advertisement for Soakum that appeared in newspapers across the country in 1915 mysteriously stated, “In ‘Soa Kum’ [sic] one tries to hit all kinds of heads for all kinds of prizes.” A contemporaneous magazine article, shared with me by Laura Ackley, author of San Francisco’s Jewel City: The Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915, was coy about the head on the “quaint” building, yet detailed the game inside:

“This is ‘Mr. Soa Kum.’” An ad that appeared in newspapers in 1915.library of congress

“This is ‘Mr. Soa Kum.’” An ad that appeared in newspapers in 1915.library of congress

There is a large figure on the right, forming the front of a quaint building, over which are the letters “Soakum”…. A line of dummy figures, representing all nations, file out of a swinging door, walk along a painted street and into another doorway…. Well, if there is any nationality that you are down on, be it Irish, German or Chinese, you get so many base balls [sic] for a dime and you “soakum” to your heart’s content.

“Looks easy, but just try it,” the article concluded. Players who knocked a hat off one of the ethnic targets would receive a cigar. (“Quality not guaranteed.”) The Exposition’s official historian, Frank Morton Todd, described the contest, known as the Kelly Game, similarly: “A row of grotesque lay figures walked out of a door, across the back of the scene and disappeared through another door, and the investor was allowed a certain number of balls for a nickel to throw at the hats as they went by. The proprietor paid a cigar for every hat knocked off.”

This misanthropic game recalls the mantra of the “equal-opportunity offender,” as uttered by W.C. Fields: “I am free of all prejudice. I hate everyone equally.” The Kelly Game was related to other ball-tossing games that used wooden heads or dolls as targets, including a similar game with detachable hats. As Fred and Mary Fried write in America’s Forgotten Folk Arts, these targets were often “stereotypes of the black, the Semite, the Irish, the devil, the police, the military, and others.” It’s not clear if black figures were among the Kelly Game’s targets.

Who was behind it?

According to documents in the exposition archives at the University of California, Berkeley, the African Dip and Soakum were registered to Herbert George Washington Meyerfeld,  Herbert G.W. Meyerfeldgoogle books the scion of a prominent entertainment family. The “popular young San Franciscan” was known for producing concerts and recitals, as well as managing at least two restaurants. His uncle was Morris Meyerfeld, Jr., who ran the Orpheum Theatre and the national variety circuit of the same name. (An African-American comedy duo, Miller and Lyles, did a routine called the “African Dip” on the Orpheum bill in 1914; the Los Angeles Herald found it “a scream.”*) * Miller and Lyles later wrote and performed in Shuffle Along, a successful early 1920s musical with music by Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle. The “African Dip” was the show’s finale.Morris, “the Rockefeller of vaudeville,” was also a subdirector of the Exposition and a member of the concessions committee that oversaw the development of the Joy Zone.

Herbert G.W. Meyerfeldgoogle books the scion of a prominent entertainment family. The “popular young San Franciscan” was known for producing concerts and recitals, as well as managing at least two restaurants. His uncle was Morris Meyerfeld, Jr., who ran the Orpheum Theatre and the national variety circuit of the same name. (An African-American comedy duo, Miller and Lyles, did a routine called the “African Dip” on the Orpheum bill in 1914; the Los Angeles Herald found it “a scream.”*) * Miller and Lyles later wrote and performed in Shuffle Along, a successful early 1920s musical with music by Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle. The “African Dip” was the show’s finale.Morris, “the Rockefeller of vaudeville,” was also a subdirector of the Exposition and a member of the concessions committee that oversaw the development of the Joy Zone.

While the monumental courts and palaces of the exposition’s “Jewel City” celebrated art, culture, and progress, the Joy Zone was an unabashedly cheesy attempt to amuse the masses and make a buck. Apparently this split was also embodied by Herbert Meyerfeld—a man of refinement but also an impresario who clearly recognized the importance of a spectacle.

The crass showmanship and casual racism of Meyerfeld’s attraction were evident at a parade in January 1915, where the African Dip was promoted with an appearance by Harry “Ki Ki”  Harry “Ki Ki” Blitzlibrary of congressBlitz, a white sideshow performer. The gibberish-spewing Blitz was known variously as a “monkey man,” “wild man,” or “Haba Haba man.”** Some have speculated that “hubba hubba” can be traced back to Blitz’s nonsense cry of “haba haba.” Blitz also ate fire, which killed his taste buds. “Pie, meat, and beer all taste alike,” he told a newspaper in 1915. “That’s one of the real regrets of my life.” As one article described his act, he went “bedecked in proper barbarian apparel, blackened face, several gee strings and armlets and leglets and earrings, and a most ferociously inane expression.” In short, he was a flesh-and-blood incarnation of the caricature on top of the African Dip.

Harry “Ki Ki” Blitzlibrary of congressBlitz, a white sideshow performer. The gibberish-spewing Blitz was known variously as a “monkey man,” “wild man,” or “Haba Haba man.”** Some have speculated that “hubba hubba” can be traced back to Blitz’s nonsense cry of “haba haba.” Blitz also ate fire, which killed his taste buds. “Pie, meat, and beer all taste alike,” he told a newspaper in 1915. “That’s one of the real regrets of my life.” As one article described his act, he went “bedecked in proper barbarian apparel, blackened face, several gee strings and armlets and leglets and earrings, and a most ferociously inane expression.” In short, he was a flesh-and-blood incarnation of the caricature on top of the African Dip.

There is no record of who conceived of the plaster head atop the African Dip, a well-crafted expression of what David Pilgrm, the founder of the Jim Crow Museum, calls “the creative energy that often lurks behind racism.” Archived paperwork names William C. Hays as the attraction’s architect*, * Hays went on to teach architecture at Cal for many years and design buildings for the UC system. though his exact role isn’t spelled out. The head of the expo’s concessions division, Todd wrote, “properly insisted” that the front of the Zone’s attractions “should be fantastic, and that each should express without any reading sign if possible, what was offered inside.” Whoever designed the African Dip and Soakum’s façades may have had these visual criteria in mind—even if the final result was misleading.

Unanswered questions

From the outside, everything about the African Dip—the name, the blatantly racialized come-on—promised a well-known game targeting African-Americans. Why didn’t it?

Is it possible that the attraction was originally conceived as a dunk tank and then switched to the slightly less tasteless Kelly Game, perhaps in response to criticism? There isn’t any indication that the African Dip sparked controversy or complaint. As historian Abigail M. Markwyn notes, there is no record of the local African-American community publicly protesting against it.* *The local branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People did object to the showing of D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, which played in the Bay Area throughout 1915.(Besides, the Expo’s white directors “had already demonstrated a lack of interest in dealing with them.”) And obviously, many whites found it unremarkable.

The African Dip and Soakum were far from being blots on an otherwise enlightened event. The Panama-Pacific Exposition had its share of racially loaded and explicitly white supremacist attractions. Just feet from the African Dip was Dixie Land, a theater topped with cartoonish minstrel  Soakum and other attractions in the Joy Zone san francisco public libraryand pickaninny characters and a giant slice of watermelon. Inside, customers could listen to “southern darkies sing the songs of old plantation days.”

Soakum and other attractions in the Joy Zone san francisco public libraryand pickaninny characters and a giant slice of watermelon. Inside, customers could listen to “southern darkies sing the songs of old plantation days.”

The Joy Zone also included Underground Chinatown, a sensationalist exhibit of opium dens and white slavery. After the Chinese government objected to these stereotypes, it was briefly closed and repackaged as Underground Slumming. A simulated Somali Village promised a tribe of “cannibal head hunters.” When it flopped, its 31 residents were evicted, detained on Angel Island, and deported. And outside the Zone, the Palace of Education included a Race Betterment exhibit, which promoted “personal hygiene and race hygiene, or eugenics, as methods of race improvement.”

Despite their attempt to profit from white fairgoers’ prejudices, the African Dip and Soakum proved commercial failures. In his official post-mortem of the Exposition, Todd described them as embarrassing flops,* * According to the expo’s books, the two “ball throwing” concessions brought in a bit more than $5,100 before expenses—about $120,000 in current money.not even mentioning them by name. Nonetheless, he wrote, the Kelly Game “made such a strong appeal to certain individuals that it deserves a place among the Zone mysteries.” He continued:

A tall, stiff hat is a temptation, and probably a majority of mankind has the hunger to throw some missile at it, so it appealed to a rather general instinct. There were people in whom the desire to knock off Kelly’s hat was so strong that they would invest ten or fifteen dollars at a time in its gratification. One enduring enthusiast is said to have spent $37 at one visit. If he did, he had something better than an iron arm. But there were not enough patrons, or their arms gave out too soon, to make this concession very lucrative.

“It was little solace to go up on the Zone and throw balls at Kelly’s hat,” Todd sniffed.

The African Dip’s mediocre run was probably nothing more than bad luck; many concessions on the Zone were a bust. Yet is it possible to see it as a rebuke, a rejection of its unapologetic offensiveness? That may be giving the white San Franciscans of the time too much credit. But it does seem clear that after the African Dip and Soakum were demolished in early 1916, they were largely—perhaps eagerly—forgotten.

View of the African Dip, Ostrich Farm, Dixie Land (far right), and other Joy Zone attractions.san francisco public library

View of the African Dip, Ostrich Farm, Dixie Land (far right), and other Joy Zone attractions.san francisco public library